To recap Part I, where we began talking about Aristotle‘s theoretical take on fanfic:

—Squick and squee are really cool words! (I don’t entirely understand them, yet—for instance, are there gradations of squickedness, or is it an absolute?)

—Ellen Fremedon still hasn’t written that essay. It’s curling season, I’m given to understand, which means she’s gallivanting about the countryside sweeping ice and zooming big rocks-with-handles around trying to hit the other guy’s big rocks-with-handles.

—Aristotle discussed the ideas expressed by squick and squee (but without the part about curling) in <cite>The Poetics</cite> where he said some interesting and provocative things that <em>still </em>influence how we think about art, theater, music, and writing.

_______________________________________

There are a couple of ideas we touched on in the beginning that now we need to identify and specifically name, for the sake of this conversation—catharsis and mimesis.

I’m not going to try to nail down single-line definitions of these concepts, since any good dictionary will do that in fairly functional fashion. But they are ideas to keep in mind as we roar onward, wind in our hair, to talk about Aristotle and squeeeeeee!

Also, please keep in mind that where Aristotle uses “poet” I’m perfectly comfortable swapping it out for the word “writer.”

_______________________________________

What separates a poet from someone who writes in verse towards other ends is sort of The Big Question, to Aristotle, in many ways. It’s the “what is art” question:

Quote:

Even when a treatise on medicine or natural science is brought out in verse, the name of poet is by custom given to the author; and yet Homer and Empedocles have nothing in common but the meter, so that it would be right to call the one poet, the other physicist rather than poet. On the same principle, even if a writer in his poetic imitation were to combine all meters, as Chaeremon did in his Centaur, which is a medley composed of meters of all kinds, we should bring him too under the general term poet. (Poetics I—about paragraph 5, depending on your translation).

So there’s the question begged, really, right? Even if the technique is not pure nor perfect, sometimes it’s art anyway. And even if the technique is both pure and perfect, sometimes it’s still not art.

So, for example, The Da Vinci Code can be said to have more in common with the Seattle phonebook than with . . . Well, no. Maybe I don’t want to go there, after all.

What’s the difference between a limerick and a poem? Because there does indeed seem to be a difference. Similarly, there’s a difference between the story you tell your spouse about your awful day, and a story told to transport a reader into another time and place.

But if poetry is something greater than technique, and greater than imitation, what exactly is it? Even if we stipulate this as true (which is a bit of a leap) I don’t know as there are any completely satisfactory answers for that question, mind you—and Aristotle doesn’t seem that sure, frankly, either. Though he does offer some ideas:

Quote:

It is, moreover, evident from what has been said, that it is not the function of the poet to relate what has happened, but what may happen—what is possible according to the law of probability or necessity. The poet and the historian differ not by writing in verse or in prose. The work of Herodotus might be put into verse, and it would still be a species of history, with meter no less than without it. The true difference is that one relates what has happened, the other what may happen. Poetry, therefore, is a more philosophical and a higher thing than history: for poetry tends to express the universal, history the particular. By the universal I mean how a person of a certain type on occasion speak or act, according to the law of probability or necessity; and it is this universality at which poetry aims in the names she attaches to the personages. (IX)

So logic, consistency, and (at least some) predictability are a Big Deal, because that’s how the audience can engage with the work. And it’s important that the audience can recognize what’s going on, at least unconsciously, because otherwise it’s no longer an imitation of something real. If it’s not about something real, then it’s something else, for Aristotle, and not poetry.

As a reader-participant-audience member, we have to be able to recognize what’s happening and understand not only the events, but the implications.

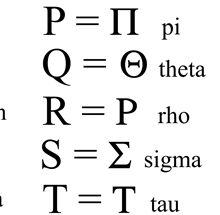

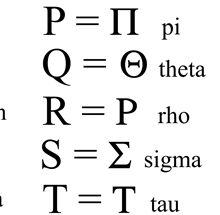

Aristotle gets a little weird when he starts making value judgments about superior and inferior ways and means of conveying this “imitation.” He gets even weirder when he wants to break poetry down into its smallest component parts—letters—and somehow find art and truth and beauty inside, like a mechanic looking under a hood. He gets whacked on quite a lot for this—it’s worth pointing out, though, that classical Greek is particulate, the words, parsable by letter the Greek alphabet itself conveys ideas by the very shape of the letters:

In my admittedly modern reading of Aristotelian concepts, rather that advocating a strictly structural approach to diagnosing poetry, he’s advocating excruciating command and control of language. That is, Aristotle thinks it’s really important to figure out how to do this ambitious thing—convey truth—deliberately and carefully, for best effect.

Structure matters. Each word must be precisely the right word, and the arrangement of the elements must draw the audience in and hold us throughout, eventually bringing us to a place of resolution and satisfaction. Therein lies a key difference between:

There was an Old Man of Kilkenny,

Who never had more than a penny;

He spent all that money,

In onions and honey,

That wayward Old Man of Kilkenny.

—Edward Lear

and

IT is an ancient Mariner,

And he stoppeth one of three.

“By thy long grey beard and glittering eye,

Now wherefore stopp’st thou me?

“The Bridegroom’s doors are opened wide,

And I am next of kin;

The guests are met, the feast is set:

May’st hear the merry din.”

—Samuel Taylor Coleridge

So Aristotle is pretty clearly onto something real when he talks about catharsis—even though the word itself isn’t present in The Poetics:

Quote:

Fear and pity may be aroused by spectacular means; but they may also<br />result from the inner structure of the piece, which is the better way, and indicates a superior poet. For the plot ought to be so constructed that, even without the aid of the eye, he who hears the tale told will thrill with horror and melt to pity at what takes Place. This is the impression we should receive from hearing the story of the Oedipus. But to produce this effect by the mere spectacle is a less artistic method, and dependent on extraneous aids. Those who employ spectacular means to create a sense not of the terrible but only of the monstrous, are strangers to the purpose of Tragedy; for we must not demand of Tragedy any and every kind of pleasure, but only that which is proper to it. And since the pleasure which the poet should afford is that which comes from pity and fear through imitation, it is evident that this quality must be impressed upon the incidents.

We might say, now, “you gotta get the audience where they live.” Which is as true of Stephen King as it was of Homer or Sophocles. That is, for a piece to work, it has to find that universal human truth that sets up a sympathetic resonance between poet and audience, so that the piece forces the listener or reader to feel something real, or the memory/shadow of something real. This is where the magic happens, and suddenly there’s something happening that transcends all the fine points of plot structure, diction, characterization, and unity.

Aristotle talked about catharsis in terms of music, in Politics, so we know he thought about it. The etymology of the word says a lot about how he thinks this all works:

“catharsis from Gk. katharsis “purging, cleansing,” from kathairein “to purify, purge,” from katharsos “pure.

From a decent essay about the Poetics:

Quote:

The word catharsis drops out of the Poetics because the word wonder, to rhaumaston, replaces it, first in chapter 9, where Aristotle argues that pity and fear arise most of all where wonder does, and finally in chapters 24 and 25, where he singles out wonder as the aim of the poetic art itself, into which the aim of tragedy in particular merges. Ask yourself how you feel at the end of a tragedy. You have witnessed horrible things and felt painful feelings, but the mark of tragedy is that it brings you out the other side. Aristotle’s use of the word catharsis is not a technical reference to purgation or purification but a beautiful metaphor for the peculiar tragic pleasure, the feeling of being washed or cleansed.

This section of the Poetics is particularly relevant in terms of squick and squee buttons. In fiction, for instance, a successful piece of writing can find your squick button and make you like it—because it’s ultimately about human truth: we’re attracted and repelled by the blood mingled with rain on the pavement and the flashing lights from the emergency vehicles, because “oh my god that could be me…” but then, to push it even a step further, “and what is that thing crouched in the driver’s seat . . ? And is it eating . . . ohmygod it is!”

That’s the “pity and fear” part of the reader/writer exchange—empathy and identification.

When a written work gives that to us, it’s enormously gratifying. We can try out these emotions in a safe context, and we understand ourselves and the world all the better for it

Let’s return to this quote from The Poetics:

Poetry in general seems to have sprung from two causes, each of them lying deep in our nature. First, the instinct of imitation is implanted in man from childhood, one difference between him and other animals being that he is the most imitative of living creatures, and through imitation learns his earliest lessons; and no less universal is the pleasure felt in things imitated. (IV)

Aristotle takes as given the concept of art imitating life, mimesis, and the Poetics is primarily preoccupied with the mechanics of how that works, and how a poem or song or play or painting is made—and what constitutes success. And if indeed, poetry (or fiction, now, since we’ve broadened our understanding of story) is about imitating life, then it very much is a process of discovery, right?

Because at its very best, a story says something true. Or rather, more accurately, something True. That truth is already existent and external to the not-yet-created text. It just is. That means it’s got to be something intrinsic to human experience—something we all can know, and acknowledge, and can understand—even if it’s at first unfamiliar. At some point, we should recognize, “Ah, yes. I know this truth. This is exactly how it really is.”

And simultaneously, while discovering and revealing extant human truth, writing—and reading—is a constructive act. You might not know the story yet, it might still be waiting for you to discover it, but if you can only reach that story through that subconscious place where you know. . . then you must bridge somehow between that place in your brain, and the part of the story that lives in the black marks on the page.

Because the truth the story or poem tells to us is already there. It exists, with or without the frame of the words and the story. The more perfectly framed and expressed, though, the better the imitation. The more perfect the picture not just of the world inside the story, that is, not just the constructed details of economics and clothing and characters and landscape—but of something much more abstract and important, something humanly True—the more perfect that word-picture, the more accessible the underlying and informing reality becomes.

Mimesis

_______________________________________

Part III coming soon . . .